INDOMITABLE SPIRIT

2nd Dan Black Belt

World Taekwondo Federation

2nd Dan Black Belt

Korea Tang Soo Do Association

World Moo Duk Kwan Federation

World Taekwondo Federation

2nd Dan Black Belt

Korea Tang Soo Do Association

World Moo Duk Kwan Federation

DEDICATION

To Grandmaster Sun Hwan Chung.

Your wisdom, insight, and patience changed my life.

Thank you for being an incredible mentor and very good friend.

Moo Sool!!

Your wisdom, insight, and patience changed my life.

Thank you for being an incredible mentor and very good friend.

Moo Sool!!

What

is indomitable spirit?

The

dedicated pursuit of goals despite obstacles.

Bong

Soo Han

Ninth Dan Hapkido Grandmaster

Ninth Dan Hapkido Grandmaster

Black

Belt Magazine Interview

PREFACE

This

document is an account of my journey, as

a middle-aged executive and father of two kids, toward earning a black

belt in Taekwondo. At forty years of age, and at my mid-life

crossroads, I made the decision to pursue a goal that I had desired

since

childhood. This blog is a chronology of personal jottings, a

journal –

each entry recalling the step-by-step process I experienced along the

way. Some events were humbling. Some were embarrassing. Most were

enlightening. All of them have helped shape who I have

become as a martial artist. It is my

hope that the older martial arts student can learn from my mistakes and

tribulations.

In addition, as I continued down the martial

path, I found myself reflecting upon the origins, philosophy, and future

directions of Taekwondo. This led to

further research into the discipline and how it relates to other traditional

martial arts. I have observed that,

while basking in the glow of tremendous growth and popularity, Taekwondo is

also at a major crossroads. It has

become the most practiced martial art in the United States, in no small part due

to its emergence as an Olympic sport. At

the same time, these same aspects that are making it successful as a sport are

potentially endangering the heart and spirit of the discipline.

It is my hope that the reader will gain an

appreciation for both the challenges faced by the student… and by the martial

art… as they continue on their journey in the future.

One final note. The reader will observe that several terms, such as 'poomse' (poomsae) have multiple correct spellings. This is due to phonetic translation between languages. The spelling of the term Taekwondo has actually evolved over the years. Taekwon-Do is the oldest and most traditional spelling, followed by Tae Kwon Do, and then the most current version ... Taekwondo.

Tom Olin

Original publication. Autumn 2004

(Re-edited and updated for website 2024)

INDOMITABLE SPIRIT

Man’s life is like making a long journey with

a heavy burden.

One must not hurry.

Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu

Chapter One – White Belt

Who

would have guessed that a semi-retired former executive and forty-year old father

of two daughters would have taken up Taekwondo?

A

handful of years ago, I was President and CEO of a midsized national food

products company. I had spent the last

twenty years of my life either behind a desk or in airport club rooms. There was virtually no time for any physical

conditioning or personal development. Exercise, for me was running from one end of the O’Hare United Air Lines

concourse to the other to catch the last flight of the day.

I

was fortunate to have traveled a great portion of the world as well as all

fifty states in the course of running my business. Many times, in some surprising places, I

would cross paths with martial arts. I would often drive by small training studios located near our company

distributor warehouses. I would catch

myself looking with interest through the painted windows to watch the

practitioners inside. I

also met the occasional movie star martial artist at corporate trade shows in Chicago, Dallas, and Los Angeles. They looked and acted so normal,

so humane, when I shook their hands. Their eyes, however, were often steely and reflective of the warrior

spirit within.

Several

events took place over the course of three years, between 1996 and 1998, that

eventually led to the acquisition of my company. On one November day, after a twenty year

career and at forty years of age, I was no longer a corporate

executive. I was now just a humble Dad

driving his kids to school every day. I

sat for many hours at home, reflecting on what I would do with the second half

of my life. I wrote down a set of priorities that included learning Spanish,

reading the Bible from cover to cover,

mastering guitar, spending more

time in charitable and volunteer work, traveling to every continent, and

obtaining a black belt in the martial arts. I set about reaching those goals. I attended Spanish classes at the local community college and I joined a

local rock and roll band.

But

I was intimidated to pursue the martial arts.

I was well past my prime physically and was at least twenty pounds overweight. I also had a well-developed sense of pride

and I feared how bad I might look on the training floor.

Interestingly,

my daughter, Laura, began taking classes at Chung’s Tiger Tae Kwon Do

Academy in Richland, Michigan. We had signed her up as a way to

keep her physically active and mentally disciplined. Several of our neighbor’s kids were taking

classes and their parents were enthusiastic about the program. So

in March of 2000, Laura attended her first class. She was very proud of her clean white “do

bok” (uniform) and matching white belt. Sitting silently in the back of the gym, I noticed that she was very

skilled right from the start and I was amazed at how focused and disciplined

she was in front of Master Choi.

Master Moses I Choi managed the “do jang” (gym) where Laura attends classes. He is a 5th Dan black belt in Taekwondo, Korean national champion in both Tae Kwon Do and kickboxing, and a master at Hap Ki Do. He is a slender six-foot Korean in his late twenties. He speaks English very well but when speaking to Grandmaster Chung or on the phone he speaks his native Korean. Master Choi is a terrific children’s instructor. He commands attention without seeming overbearing. He makes the students take the martial arts seriously but the hint of a smile keeps things on the light side.

Watching

Laura throw side kicks and practice her poomse (forms) immediately reminded me

of the martial arts that I practiced years ... many years ... ago. I remember the classes that my father and I

attended at the YMCA in Ashland,

Ohio. I was fourteen years old at that time. Dad felt that these classes might help me

build confidence. The discipline that we studied was Kenpo Karate. Our

instructor’s name was Bob Mazzotta. He

was a ruddy-complected brute. He had a

partner, I think his name was Dan, who specialized in a new form of martial

arts that emphasized kicking called Tang Soo Do. Dan’s feet were hard as rock. He said that he had trained in the Far East during his stint in Vietnam.

Dad

and I took classes for a few months and my interest in the martial arts grew

rapidly. At the close of the program I

tested for and received a green belt. I

earned this by executing a handful of Katas (Japanese forms) and breaking some

boards. Our instructor told us that we

could continue taking classes from him personally for twenty dollars an

hour. At that point, we could not afford

to continue with the program and I no longer stayed with it officially.

Unofficially,

however, I continued to study Karate. I

bought several books on the subject and remember one good one by Bruce Tegner,

which became dog-eared and wrinkled by constant use.

I kept a kicking target in the basement and

worked out regularly. I thought that I

was becoming pretty proficient until I saw some pictures that Dad had taken of

me doing kicks in the living room. One

photo looked like I was stamping out cockroaches. I was shamed and humiliated and my interest

faded quickly.

As

a side note, I later found out that my first martial arts instructor (Bob) was arrested

for hiring a person to throw battery acid in his wife’s face. He went to prison.

That great

dust heap called “history.”

Augustine

Birrell

There

was another moment, a real short one, when I again signed up for Kenpo Karate classes

in Columbus, Ohio. This was with the famous teacher Jay T. Will (Black Belt Hall of Fame

1976 and student of Ed Parker). I

attended three classes at his downtown SW 5th Avenue location and found I was so out of shape that I could not

keep up with the intense classes. The mind

was willing but the body not so! In addition, the fact that we lived twenty

miles away and I was in the midst of rigorous graduate school studies at Ohio State

University snuffed that

venture out very quickly. I did get a

cool uniform out of it though.

Three years later, Jay T. Will was arrested with two and a half pounds of 90 percent pure cocaine at his dojo. He spent the next several years at the Federal Correctional Institution in Terre Haute, Indiana. Kenpo Karate, it seemed, was not a good character builder.

I maintained

an interest in the martial arts. Even as late as 1998, my wife, Tam, and

I took some Tai Chi classes at the Borgess

Health Center

in Kalamazoo. I could visualize myself doing the smooth and

fluid moves that we once saw hundreds of people doing in the park one crisp Sunday

morning near the Temple

of Heaven in Beijing on a recent vacation

in China.

However, the instructor for the workshop was not qualified and the classes were canceled as students dropped out.

When the

student is ready, the master appears.

Buddhist

Proverb

So

here I was, sitting in the back of Chung’s Tiger Tae Kwon Do Academy, watching

Laura go at it and I began to get the itch again. I casually grabbed one of the pamphlets in the rack on

the wall and began to read about Grandmaster

James Sunhwan Chung. He was a 9th

degree black belt in Korean Tae Kwon Do and a 9th degree black belt

in Hap Ki Do. There were pictures of him

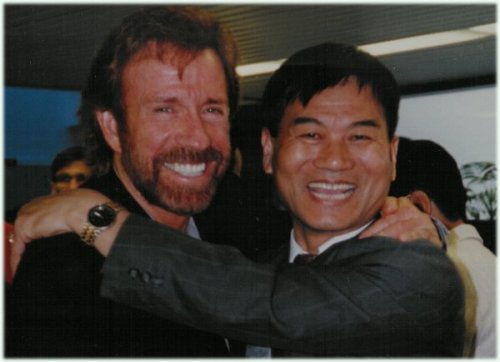

on the wall with Chuck Norris and Bill Wallace.

There were still more pictures of him - with cars driving over his chest, breaking stacks of bricks, walking across broken glass with buckets of water hanging from needles that pierced his neck and arms. Yes, this was my destiny!

There were still more pictures of him - with cars driving over his chest, breaking stacks of bricks, walking across broken glass with buckets of water hanging from needles that pierced his neck and arms. Yes, this was my destiny! I just had to meet this amazing man.

Traditional Taekwon-Do Magazine Cover Story

"Incredible Sun Hwan Chung Tells His Story"

So,

ready or not, I called the “World Headquarters” in Kalamazoo. The Grandmaster answered the phone himself. I introduced myself and asked if I could talk

about family membership possibilities. Mr. Chung suggested that I come in and talk with him.

The

next morning, I drove to Chung’s Black Belt Academy on Stadium Drive in Kalamazoo on a quest to

discover more. The studio itself was a

wood-sided stand-alone building, with at least five or six signs on it

proclaiming this to be Chung’s Black

Belt Academy.

It shared a parking lot with Sweetwater’s Donut Shop. There was a large Chung’s sign at the

street. On that sign it said “Discipline,

Confidence”.

As

I approached the front door, I noticed a sign indicating that the parking spot

directly in front of the front door belonged to the Grandmaster. I also noted several signs that proclaimed

that all shoes were to be removed and placed in a rack by the front door. Having developed an appreciation for far

eastern cultures in my travels, my interest was piqued and I obliged. Upon entering, I noticed that the facility

was actually two gyms. There was a

smaller carpeted room near the entry and a larger one, located to the side, that seemed newer with a hard tiled

floor. Every inch of the perimeter of

the small room was covered with martial arts awards and trophies. Some of them were six or seven feet

high. Mounted along the wall, near the

ceiling were the certificates of at least thirty black belts. I was pleased to see that several of them

featured people in their thirties and even a couple in their forties.

|

| Grandmaster Sun Hwan Chung |

I

can’t remember if there was a receptionist when I arrived but I do remember

that I could see Mr. Chung at his desk in an office in the back corner. He noticed my arrival and stepped out to

welcome me. He looked almost exactly like the pictures on the wall except that

the mustache was gone and he appeared slightly older and gentler. He brought me into his office, which was

crowded with awards, plaques, and other honors.

He

asked if I was interested in practicing Taekwondo. For some reason, probably because of my lack

of confidence, I launched into a diatribe about my experience in the martial arts. Of course, I literally hadn’t lifted my foot

above my knee (other than to get into the hot tub) in almost twenty years. He graciously nodded and welcomed my history

as if it really meant something. I asked

if I had to do any full-contact fighting with people half my age. I also asked if there was a special program

for older students. He sensed my

apprehension and calmly stated that I could achieve a black belt. He said that he would not measure me against

other students but on my own mental discipline and what I could achieve with my

own physical limitations. The

Grandmaster told me a story about a doctor my age that was similarly concerned

but recently earned his black belt.

I

told him that my daughter Laura was already taking classes at the branch in Richland and inquired

about family memberships. He mentioned

that indeed there were such memberships and

that he would even deduct Laura’s initial payment from the tab. He asked if I would rather take classes in Richland at the local do

jang. I told him that I wanted to take

my classes in the morning, which was true. But more than that, I also didn’t want the humiliation of standing there

at the Richland

do jang in my clean white uniform and snow-white belt while many of my friends

picked up their kids following their after-school class. Another consideration was that I wanted to take my classes directly from

the Grandmaster and thought that attending lessons in Kalamazoo would help facilitate that.

Mr.

Chung was tremendously gracious and patient as I whipped out the credit

card. April 24, 2000.

Teachers

open the door, but you must enter by yourself.

Chinese

Proverb

He

then asked me when I would be interested in getting started. All of a sudden, a shiver ran down my spine. What had I just done. Oh my God, I’m committed now. He suggested that he might give me my first

couple of lessons to get things off to a smooth start. He took me out of his

office and handed me three uniforms (do boks), one each for my wife Tam and older

daughter Michelle, and one for me. He

very kindly gave me a white pullover uniform with a black collar on it. I think that it signified that I paid a lot

of money or something akin to it. Anyway, I was glad to have a uniform with some black on it.

Now,

I had to go home and tell Tam that we were all committed – after all I

had just signed up for the “family” membership. She was very supportive, as long as we

remembered that we started this whole thing for Laura.

The

next morning I arrived bright and early for my first class with the

Grandmaster. He led me to the locker

room where I changed into my do bok. I

remember looking into the mirror on the way out to the gym and saying to myself

“Here we go.” I also remember how

nervous and embarrassed I was to walk out in a perfectly white uniform, with

the creases still in it, and looking down at that bleached white belt - which

signified purity. The road to a black

belt seemed as far as the moon.

My

first objective was to show Grandmaster Chung how good I was in the martial

arts…like I could remember any of it after twenty-five years. I wanted to show

him some of my forms or anything that might impress him. He calmly began some loosening up exercises

and quickly moved into some stretching. I had already broken into a sweat in the locker room and by now I was

starting to breathe heavy. By the time he had me grab the horizontal bar along

the wall, the sweat was rolling off me onto the floor and my lungs were

screaming. I looked at the clock. We had been at it for five minutes.

We

moved into the center of the floor where we did some vertical leg

stretch-kicks. The Grandmaster showed me

how to do them by flinging his legs straight up over his head. I started slowly, but then soon I was kicking

over my head. I noticed that with each

kick I felt small rips in the backs of my leg muscles - but hey, I was showing

this guy that I could do something!! We

moved over to the kicking bags. They are

like a plastic buoy filled with water as ballast and with a large padded cover. The idea is that you kick them hard enough to scoot them across the floor. He had me practice front kicks. My adrenaline was rushing and I wanted to

show him how powerful I was so I kicked that bag across the floor at least

twelve times. The balls of my feet and

my toes started to hurt. Grandmaster

Chung made a comment about how powerful I was; which made me kick the bag even

harder! Just as my feet were about to

explode, the lesson was over. The

Grandmaster closed the class with meditation and an “appreciation form." He very kindly expressed his appreciation for

my effort and welcomed me again.

My

body started to go into rigor mortis as I walked out to the car in the parking

lot. I drove home and lay on the bed for

an hour. Then I went into the hot tub

and blew the jets on my hips for twenty minutes.

There is a

well-known story of a Japanese Zen master who received a university professor

who had come to inquire about Zen.

Shortly into

the discussion, it was obvious to the master that the professor was not so much

interested in learning about Zen as he was in impressing the master with his

own opinions and knowledge. The master

listened patiently and finally suggested that they have tea. The master poured his cup full and then kept

pouring. The professor watched the cup

overflowing until he could no longer restrain himself. “The cup is overfull, no more will go in” he

said.

“Like this

cup,” the master said, “you are full of your own opinions and

speculations. How can I show you Zen

unless you first empty your cup?”

With

an “empty cup” and a little more humility, my next class with Grandmaster Chung

went well. He started to teach me some

poomse (forms) and self-defense techniques. I think that he might have noted my soreness and spent the class on

aspects not so strenuous.

The

next Monday, I arrived just as Grandmaster Chung and Master Choi had opened the

do jang and were still drinking coffee from Sweetwater’s Donut shop next door. I had mistakenly thought that there was a 9:00am class. Grandmaster Chung kindly instructed Master

Choi to give me a “private” lesson. I heard him tell Master Choi to “take it

easy” because it was only my third class. Well, I had seen Master Choi teach Laura before so I was confident that

there would be no problem. Three minutes

and fifty judo pushups later, I learned another great lesson of the martial

arts - never show up for a class that doesn’t exist.

Soon,

Master Choi had me doing crescent kicks over a three-foot high kicking

dummy. One hundred repetitions with each

leg. At forty, my legs went numb. At sixty, I couldn’t lift them. At eighty, I had lost all sense of control

and balance. I can’t remember if I made all one hundred with each leg because I

started to get light-headed. After the

hardest physical hour of my entire life, and forty more judo pushups, I crawled

home.

The next day, I realized that I had

done something seriously wrong. I could

hardly walk and the muscles inside my legs, near my groin, were shredded. I was physically unable to get around let

alone take classes for four days.

On

my first day back, Master Choi asked stiffly, “Where were you this week?” I told him of my condition. He responded as if he had heard that story a

hundred times before and sharply told me to take it a little easier in class. I felt like a total dweeb. Three classes and I’m fingered as a

lightweight.

Over

time, I slowly established a rhythm and was going three times per week. Some of my past martial arts experience was

paying off. I remembered how to snap

into front and back stances that were similar to the ones I learned years ago.

In fact, some of the poomse forms were identical. Interestingly, the Grandmaster noticed my

technique and mentioned that they were older, more formal, ones.

My

confidence began to grow but I still despised the color of my belt. As a white

belt, my goal was to obtain a purple belt as quickly as possible, mostly because

it was the first dark-colored belt in the system of ranking. That was two steps away. I hated being a white belt. I hated having to stand in the left-hand rear

of the class, especially when I looked around and saw children with brown belts

running around with their Nintendos and jumping on all the equipment. These were not the ruminations of someone

with great wisdom or mental discipline. I knew that I had a long way to go.

Chapter

Two – Yellow Belt

My

first belt test took place on a warm Saturday morning at the main do jang on Stadium Drive. I

was unbelievably nervous and stressed. I

knew my stuff, but was I good enough? How harsh would they grade me? Would I fail? These worries turned out to be

unwarranted. I earned my yellow

belt. But more importantly, I was able

to watch the higher belts go through their tests. Belt test day turned out to be a great

learning experience in itself. It was

also wonderful to witness Laura as she passed her test for her purple belt.

In

order to qualify for a black belt at Chung’s Black Belt Academy, a student must

participate in at least six tournaments. These tournaments involve practicing forms but mainly emphasize

Olympic-style sparring. These are full-contact exercises where knockouts are

not uncommon. I assessed very quickly that I needed to get this experience out

of the way before I became too highly ranked and got my butt kicked.

The

Great Lakes Cup was held in Lansing,

Michigan on June 24, 2000 at the Lansing Community College

gymnasium. I was sweating profusely as I

entered the gym and saw hundreds of competitors in various uniforms and

belts. I was entered in the Senior

Division, meaning combatants 35 years old and older. I was too intimidated to sign up for sparring

but thought I would try the forms competition.

As

I warmed up, I saw a guy about six foot six and at least 250 pounds practicing

roundhouse kicks into a bag. With each

kick came a shout so loud that rattled the rafters. The bag keeled over with

each tremendous blast. The guy even wore

a black uniform, which made him appear even more sinister. I asked somebody about that guy. He was 36 years old. Oh no!!

Wait a minute ... I’m not sparring. I took a big sigh of relief. I

pitied the poor guy that had to fight that monster.

As

it turned out, I competed against eight other people in the forms

competition. Most were older than me,

like maybe in their fifties. But there

was this one nerdly looking guy from Indianapolis

with weird goggles and a skinner haircut.

He had a gut and appeared to be very uncoordinated. So I figured I had a good chance to do

well. We were tested two at a time – and

my form was nearly perfect. The judges

announced that I was tied for first place ... with the nerdy guy! I was excited that I had done so well and was

sure that I could beat him. We had to

repeat our forms in a runoff simultaneously for the judges. I had performed yellow belt form number four

– a Tang Soo Do poomse that featured a good mix of kicks, blocks, and

punches. I noticed that my opponent

performed a very short and simple poomse that featured no kicks at all. I thought, “This thing was in the bag!!”

We

started together, everything was going great, until I turned around halfway

through my form and saw that he had already finished his form. Somehow seeing

this broke my concentration and I made a glitch in my form. A small glitch, but not small enough for the

judges not to see... and it happened two moves from the end. I bowed afterward in disgust having lost my

concentration so easily. In just a few

seconds it was over. I am standing there

with a second place trophy. I had just

lost to the nerd from Indianapolis. I pounded on myself mentally the rest of the

weekend. Obviously, I was too

competitive for my own good and I learned that with whatever skills I acquired

in my classes, I had yet to acquire wisdom or patience.

He who only knows victory and does not know defeat will fare badly.

Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu

I stayed at the tournament to watch the sparring contests. They were every bit as tough as I had imagined. One competitor from our do jang, his name was Adam, fought three bouts in row. He injured his hip in the second fight when he fell out of the ring and into the corner of the judge's table. In the gold medal bout, his opponent had astutely seen where Adam was hurting and promptly went about kicking Adam’s hip like a jackhammer. Adam gamely put up a great effort but the injury and three consecutive fights in a row took their toll and he was vanquished. I learned much from what I saw...and it told me that I’d better get my bouts in soon.

Something

else I noticed too. It seemed that most

of the other do jangs had quite different ideologies than ours and it seemed

like martial arts today had taken on a different dimension since I had studied

it as a kid. Most organizations today appear

to be almost totally focused on competition and Olympic-style sparring. Teachers

focused for hour upon hour in repetition - kicks, punches, kicks, punches –

coached almost as if Taekwondo were a sport, like baseball, football, or

soccer. Gone was the spirituality and depth of the art. For them, it seemed like it was all about

winning contests. Seeing this for the first

time was enlightening as well as disappointing and it made me reflect upon the

past, present, and future of the martial arts.

It

seems like the “westernization” of these arts has placed almost total emphasis

on the physical, most specifically, the combative or “sport” phases of the

discipline. Much of the mental and

spiritual aspects have been forgotten or ignored by those who presently

practice martial arts in the United

States. I would develop a greater understanding of this as I progressed down the

martial path.

Traditional

Tang Soo Do is not a sport.

Those

practicing traditional martial arts are training for a lifetime of victories.

Chun Sik Kim

Interview –

Tae Kwon Do Times magazine

Fortunately,

Chung’s is among the few martial arts organizations that still follows a more

traditional approach. There is a focus

on developing the whole person - body, mind, and spirit. There is physical conditioning, to be sure,

but more importantly, each practitioner is urged to develop one’s inner-selves as

well. We are given assignments to read

ranging from the philosophy of Taekwondo to the history of Korea. We are tested on this subject matter during

every belt test. We touch on deeper matters as well, such as the importance of

meditation and an understanding of Zen. Grandmaster Chung believes that the physical, the mental,

and the spiritual must all be in balance if the student is to be a true

master of the martial arts.

Chapter Three – Purple Belt

Power of the

mind is infinite while the brawn is limited.

Koichi Tohei

I

tested for my purple belt about a month after the Great Lakes Cup tournament. I was now voraciously reading all I could on

the subject of Taekwondo. I was buying

training equipment, sparring gear, and video training tapes. I acquired every

issue of Tae Kwon Do Times, Black Belt Magazine, and every other martial

arts magazine that I could lay my hands on.

There

is an ancient Chinese maxim, which says, “On ko chi shin.” This means,

“To study the old is to understand the new.” So I studied the history of Korea and its

martial arts. According to legend, Korea suffered

constant invasions from larger and more powerful kingdoms because of its

strategic centralized position in eastern Asia. Korean tribes found it necessary to develop

methods of defense based on human and animal physiology.

In

108 BC, the Korean peninsula was invaded by Chinese emperor Wu of the Han

dynasty. The Chinese were eventually

driven out of Korea,

replaced by three kingdoms – Silla, Baek Je, and Koguryo. The most loyal of these kingdoms to ancient

Korean traditions was Silla. Their king, Jin Heung, recruited and developed a

small group of warriors known as the Hwarang. Not only were they skillful in combat, they

were also highly educated in philosophy, morality, and the arts. Their skill and intelligence, combined with a

strong code of ethics, made the Hwarang a valuable asset to Silla. These warriors successfully protected Silla

for three hundred years.

Over

time, the martial arts expanded from training of the military to become regular

features of athletic competitions and festivals.

As

the Silla kingdom gave way to the Koryo dynasty, the martial arts continued to

flourish with the military and its citizenry. Now named Su Bak, these skills were taught in schools and a

unified system of teaching was organized. By the thirteenth century, Korea was under attack once again

from the Mongols and then the Japanese. Korea survived

under the military leadership of Yi Song-gye, but his strong support of

Confucianism and its pacifist philosophy led to the decline of Su Bak in the

military and as a sport. This mindset

eventually left Koreans unable to defend themselves during continued invasions

by Japan.

In

1894 and 1904, Japan

clashed with China

and Russia

in attempts to capture Korea. Japan emerged victorious and

annexed Korea. They renamed it Chosun. Japan remained in control until the

end of World War II in 1945. It was not

until after Korea

was liberated that its martial arts began to grow again in popularity.

Understanding

the true history of martial arts in Korea is made difficult by the fact

that conquering nations destroyed all things associated with the preexisting

culture, often redefining the past, and influencing the art with their own

martial customs and history.

Back

at the do jang, I was starting to get into the groove and my body was showing

marked improvement. I could kick above

my head without being sorry for it the next day. I still had difficulty with spinning back

kicks and foot speed, but my skills were coming along. I would finish practices feeling tired but

mentally fresh. I was beginning to set new goals - now that I was a purple

belt, my next goal was to earn a green belt.

One

of my responsibilities as an 8th gup is to memorize the Tenets Of

Tae Kwon Do. They are the five key

aspects that all students of this martial art must possess:

Courtesy: Politeness,

consideration of others, respectfulness.

Integrity: Personal

pride, honor, morality, wholeness.

Perseverance: Continuing

to try to achieve a goal in spite of obstacles.

Self-Control: Being

responsible for one’s own actions and behavior.

Indomitable

Spirit: Strength of

mind and soul.

During

this time, I was beginning to learn more about Grandmaster Chung. He began training in the martial arts when he

was eight years old under the guiding hands of several of the world’s earliest

and greatest Tang Soo Do masters – starting with its founder Hwang Kee, Chang Young Chong (Dan #15), Jong Soo Hong (Dan #16) and Jae Joon Kim (Dan #38 - a relative of Hwang Kee and

founder of the American Moo Duk Kwan Tang Soo Do Federation). He earned his first black belt from Hwang Kee

at age eleven. In 1965, Chung won the

Korean Tae Kwon Do National Championships, defeating eleven challengers from

all over the world. In addition, he won the Asian Championships in 1966. Throughout the late 1960s, he served as an instructor for both the Korean and the U.S. military

in Asia.

Grandmaster Koe Woong Choung in Hwang Kee's Central Station Dojang

Grandmaster

Chung was sent by Hwang Kee, in the second wave of Taekwondo masters, to the United States

on June 18, 1970.

Man Bok Song, Sun Hwan Chung, and Chung Il Kim (along with Hueng Iyol Yoon and Jin Mun Hwang) at Gimpo International Airport prior to departure to the United States (June 1970)

(Photo courtesy Moodukkwan.net)

His American sponsor was Dale Drouilard, the

first American to receive a black belt from Grandmaster Hwang. Drouilard and fellow American black belts

David Praim and Russell Hanke sponsored many Korean Masters such as Jae Joon

Kim and Sang Kyu Shim in the United

States. All of these sponsors were Michigan natives, so

this might explain why so many Korean instructors began teaching in Detroit. As a new arrival, Chung first instructed at

(Jae Joon) Kim’s Karate School in Grand River. A number of challenging and difficult months

followed, as Chung was forced to earn his credentials many times over, and he

did so very successfully and honorably.

This photograph (late 1970) shows the conclusion of the 46th Dan Shim Sa (black belt tests) that took place in the Steelworkers Union Hall in Detroit, Michigan.

Grandmaster Sun Hwan Chung is second from left, along with Grandmaster Chung Il Kim. Moo Duk Kwan founder Hwang Kee and Grandmaster Man Bok Song are awarding black belt promotions to Dale Drouillard (5th Dan), Chuck Norris (4th Dan), Pat Johnson (3rd Dan), and Loren Adams (3rd Dan).

(Photo courtesy Moodukkwan.net)

Grandmaster Sun Hwan Chung is second from left, along with Grandmaster Chung Il Kim. Moo Duk Kwan founder Hwang Kee and Grandmaster Man Bok Song are awarding black belt promotions to Dale Drouillard (5th Dan), Chuck Norris (4th Dan), Pat Johnson (3rd Dan), and Loren Adams (3rd Dan).

(Photo courtesy Moodukkwan.net)

It

was not long before Grandmaster Chung began to look across America for

opportunities to open his own school. He

first thought about Palm Beach,

Florida as a possibility, until a

hurricane arrived the same day he did. Then he looked at Miami as an option, but he noted that too

many areas were saturated in the drug trade.

instructors in the United States (far left, 1971 alumni photo)

Chung

then flew to the west coast, southern California,

where he wandered up and down Santa

Monica Boulevard, counting do jangs and dojos by

the hundreds – “one on every block.” He

stopped by the do jang of Hee Il Cho, who had just purchased his school from

Chuck Norris. Grandmaster Chung had

known Cho from his years training in Korea. This time, however, he found Cho to be

somewhat arrogant and aloof, perhaps reflecting the big city attitudes of Los Angeles. Grandmaster Chung determined from his travels

that he would be better suited if he found a medium-sized, Midwestern city to

open his new school. He eventually settled

on Kalamazoo, Michigan.

|

| Moo Duk Kwan founder Hwang Kee visiting Grandmaster Chung's Kalamazoo dojang in 1975 |

During

the next three decades, Grandmaster Chung taught thousands of students his Moo

Sool Do (Martial Arts United) mix of Taekwondo, Tang Soo Do, and Hap Ki

Do. He has made many friends in the business including some of the most famous

names in the martial arts. He counts

Jhoon Rhee, Bong Soo Han, and Chuck Norris among his friends. He has rubbed shoulders with Bill Wallace,

Benny “The Jet” Urquidez, Joe Lewis, Cynthia Rothrock, and dozens more martial

arts legends.

|

| Grandmaster Chung with martial arts superstar Chuck Norris (Taken during Norris' 9th Dan black belt presentation) |

Grandmaster

Chung is a legitimate 10th Dan black belt instructor (honorary) in the art of Moo Sool Do. He is among the elite grandmasters to have earned a 9th Dan from the Kukkiwon. He is an 9th Dan instructor in Hapkido, certified by the Korea Hap Ki Do

Association. He is a Tang Soo Do World

Master Instructor, certified by the Korea Soo Bak Do Association. He is

recognized as an International Referee by the World Taekwondo Federation and United States Taekwondo Union. He is currently a U.S.A.T. Martial Arts Commissioner. He is past president of the Michigan Tae Kwon

Do Association.

After

more than sixty years in the art of Taekwondo, Grandmaster Chung is

considered one of the five most senior World Taekwondo Federation Grandmasters on the planet. I

am tremendously privileged to be a student of such a respected and honored

Grandmaster.

Daughter

Michelle was now fully involved and moving along quickly. She was already a yellow belt. At first, she was intimidated by the thought

of combat but her flexibility (she can do a side kick above her head) and

self-discipline were truly outstanding.

By

this point, I was starting to feel pretty cocky, with my dark-colored belt and

all. I can remember distinctly one

Saturday morning during family class, I thought that I would show Master Choi a

thing or two while he was holding the handheld kicking targets. I thought that I would rip that target right

out of his hand with a roundhouse so powerful that he would never forget. I bounced a few times on my toes and then, bam!! I am not sure which toe on my right foot

broke first, my third or my fourth, but I do know that it took more them eight

weeks for them to get back to normal.

Another

rite of passage for a purple belt; I was initiated into the world of contact

sparring. I was dreading sparring for

weeks, knowing that my time was coming closer and closer. When the instructor would ask the students

what they wanted to do on any given day, all but one would say “sparring” … and

that one was me. I was quietly requesting

“forms?” I guess that I was afraid of

being beaten or humiliated. Sparring

emphasized all of the aspects of martial arts in which I was not skilled - speed,

flexibility, reaction, and aggression. I was fast approaching the part of the

discipline that I feared the most. And I hated the notion that this fear would

be exposed.

My

day came early in September and my fears were unfounded.

As

with most things in life, the worry was worse than the reality. Sparring is not

so bad once you try it. My first several

spars were awkward. I wasn’t really sure

what I was doing but neither was my opponent. As I progressed, however, I began to develop some kicking and punching

combinations. My size and power were an

advantage in my first few spars. However, one of my instructors critiqued my first efforts, stating that

I was too slow and I was trying to put too much power into my kicks. Furthermore, I was leaning into the opponent,

like boxing. This was a cardinal sin

because it is easier to get your block knocked off by a spinning back kick or

something worse. “Speed was more

important than strength,” he said.

The less

effort, the faster and more powerful you will be.

Bruce Lee

One

morning, I was paired up with an opponent half my age. He came after me with abandon and I was

caught off guard. He was scoring time

after time. As he did, my anger climbed

higher and higher. But the madder I got,

the worse I did. I was screaming with

rage. I kicked as hard as I could. I leaned into the opponent. I received a back kick to my chin. In the span of about two minutes my

confidence in sparring went from high to zero. I felt embarrassed and humiliated. Making matters worse, my right ankle had hit his elbow at one point in

the match and was swelling up quickly. I

went home beaten, both mentally and physically.

The angry

man will defeat himself in battle as well as in life.

Samurai

maxim.

I

resolved to change my methods. My

motivation was simple; change or get killed.

Two

days later, I was again matched up with the same opponent. By this time I had changed my strategy. I

stayed loose on my feet and did not think about premeditated moves. I focused on speed, rather than power. It worked. I was laying into this guy. I was

a totally different fighter. I don’t

know who won for sure, but at least I held my own. As quickly as I had lost my confidence, I had

regained it. And this came at a good

time, because I had signed up to spar in the 2000 Michigan Cup Martial Arts Tournament the

next weekend.

Chapter

Four – Orange Belt

Seeing

that Michigan Cup date on my calendar day after day was like taking a daily

dose of stress. The day finally came,

and I was sick with a cold. But by

God, I was going to dispense with one of those sparring requirements even

if I died. I arrived at the gym at 7:00am to volunteer with set up and

spent the next ten hours imagining some 250 pound guy in a black uniform

kicking the crap out of my face.

My

kids, Michelle, Laura, and I had signed up for all of the events - forms,

breaking, and sparring. The kids were up

first and did very well. Laura won gold

medals in both forms and breaking. Michelle won a gold in breaking and a silver medal in forms.

I

again competed in the Senior Division.

There were eight of us in our group.

Thank goodness the nerd from Indianapolis

wasn’t there. I was, however, one of the lowest ranking belts in the

division. At 12:00 noon

we took the floor. I was next to last in

forms so I was able to watch the other competitors perform theirs. I noted that several of them slipped up in

their forms so I felt that I had a chance to win. I was called up before the three judges and

performed Pyong-Ahn* Ee Hyung (an orange belt Tang Soo Do form). I was nervous but did well. After the final competitor, the judges stood

up and called us into positions - and they presented me with the gold medal.

* Hwang Kee claimed that the five artful and sophisticated forms known as “Pyong Ahn” (peace and confidence)

evolved from a single one hundred year-old karate kata originally

called “Jae-Nam," named after the Hwa Nam area of China, and first developed by a Mr. Idos. In actuality, he may have been speaking of Sensei Yasutsune Itosu. Itosu was an Okinawan Shorin-Ryu karate master who created the forms in 1901, naming them 'Pin An'. He influenced many of karate’s great grandmasters, including Gichin

Funokoshi – the founder of modern Shotokan karate. Hwang Kee studied these forms, modified them,

and renamed them Pyong Ahn as part of his development of Moo Do Kwan Tang Soo

Do.

Each

of us then continued with the breaking event. I broke three boards - with a ridge hand, left footed ax kick, and a

side-kick (which took two tries to break). I won the bronze medal in that event.

The

girls had interesting sparring experiences. Laura pounded some poor kid around the ring for the entire ninety

seconds but her mauling technique was not artful enough to win the gold. The judges gave the match to her opponent and

she won the silver medal. Michelle was

placed in an advanced group and sparred a girl three gups higher and two years

older. She held her own until her

opponent punched her in the mouth illegally and (despite her mouth guard) her

braces cut into her gums, causing them to bleed profusely. It was a tough

match, and Michelle earned her bronze medal. This experience was enough, however, to hurt Michelle’s desire to

continue with Taekwondo.

Having

done as well in my first two events, I didn’t feel as much pressure to win my

sparring event. And as it turned out,

there were only two of us in our gup group to spar. My first career sparring opponent was David (Walker). He was also an orange belt. He was about four inches shorter than

me. At the suggestion of the referee, we

agreed that we would focus on having a good match and keep things civil. The match began and I felt razor sharp. I was firing off left and right-footed

roundhouses. Even occasional back kicks.

I was moving him all over the ring. Was

that Bruce Lee in the ring or was it me? I could hear his instructor/coach

cheering him on but that did not matter. I was in the zone. In what seemed only

a matter of moments, it was over I was standing there with a gold medal around

my neck. A gold medal in sparring - can

you believe it!

Our

celebration was short-lived, however, when a black belt finalist was kicked in

the head and knocked to the ground and then turned blue and convulsed for five

minutes. It took almost twenty minutes

for the ambulance to arrive. He was

released from the hospital the next day, but the effects were longer lasting on

many children there who had never seen anything like that before. Standing there, I couldn’t help but think of

the black belt masters from Chicago

who were complaining at the beginning of the tournament that the rules weren’t

relaxed enough to permit knock outs at all gup ranks. I guess they got the violence that they

wanted. I hope they enjoyed it.

We

got home and reviewed the videos that my wife filmed of our events. I must admit

that I was impressed with my form and breaking events. But then I watched my

sparring performance. I started getting

sick. I looked so lethargic and

weak. I looked nothing like I felt

during the match. I learned from

this. I needed speed, speed, and more

speed. I

went to my next classes determined to build my speed skills. But let me tell you, speed drills can kill,

especially when you are over forty years old.

Something

interesting happened in my next class. Master Choi was making me do that same leg-lift over the kick bag

routine. I was struggling as I got into

the high eighties and then - boink - a leg couldn’t get over. Normally at this point I would get angry and

embarrassed. But this time I laughed. I laughed at myself. I asked Master Choi to hang in there with me

and that I would complete the exercise, which I did. But this time I did it with a smile on my

face. I knew that something had happened

here that was special. I didn’t take myself so seriously. Somehow I grew a little bit on the inside.

Five

Principles of Judo:

Carefully

observe oneself and one’s situation, carefully observe others, and carefully

observe one’s environment.

Seize the

initiative in whatever you undertake.

Consider

fully, act decisively.

Know when to

stop.

Keep to the

middle.

Jigoro Kano

1860 – 1938

Chapter

Five – Green Belt

Patience;

the essential quality of a man.

Kwai Koo-Tsu

Now

a green belt, my next focus was on attaining a brown belt. But I knew my progress in this direction

wouldn’t be so fast.

I

hate to admit it but as I was trying to open a closet door at home, I felt a

sudden deep pain in my lower back. It

felt like a muscle pull, but it seemed lower than usual. In addition, as time wore on, this pain was

accompanied with jolting nerve pain that radiated around my waist and down my

legs. I immediately knew that this was

symptomatic of sciatica. Despite this, I

jammed in two classes on Monday and Tuesday just before leaving for Atlanta to visit Tam’s

brother Mike and his wife Joyce for a golf event at their club.

As

the pain intensified the following day, I stopped on the way to the airport to

buy a back brace and I wore it on the flight. I described to Joyce, a registered nurse, my condition and she

prescribed an anti-inflammatory for me. After a few days, the pain subsided somewhat, but I could still feel

tenderness, which remained localized on my lower backbone. Did I have a slipped disc or something more

serious? Tam and I returned home Sunday

night and I hoped to resume Taekwondo classes on Tuesday. At

the time when it was necessary to step up the level of intensity and frequency

of my workouts, I had lingering doubts about the stability of my back.

You’re in pretty

good shape for the shape you are in.

Dr. Suess

I

called the local sports medicine clinic to see if they could help. The moment I mentioned “back” the

nurse said, “I’m sorry, but we don’t handle back problems here.” Then I went to my family physician and he put

me through some rudimentary stretches and motions. He was impressed with my overall flexibility and

gratefully he also noted that if I had a pinched nerve or disk problem that my

pain would be much more intense. But as

he looked further, he noted that somehow my right hip was “catching” a little

on one side. He said that my physiology was probably preventing me from increasing my flexibility ... possibly a defect known as hip dysplasia. In the end, he suggested that I had probably simply pulled a muscle in my back and that this would resolve itself after a

time. He even gave me the green light to

return to Taekwondo practices as long as I didn’t put too much stress on it. Of

course, I was at class the next day.

As

a green belt, I now had some rank, and was at times the highest-ranking gup in

the class. This role has greater

responsibility as well as clout. The

highest-ranking student almost always opens class by calling out “Charyut”

(attention), and “Kyung Yea” (salute),

“Ahn Jo” (sit down), “Moong Yum”

(meditate), “Ba Roe” (return), “Ehro Set” (stand up), and then “Sa Bum Nim Gae – Kyung Yea” (a

salute of respect to the master). This is followed by “Don Gyol” (meaning I

trust, respect, and will help you).

Being

the high-ranking belt in my class was an honor that I took seriously. I made an extra effort to greet newcomers and

helped them with questions and the techniques they were practicing. Of

course, for me (Mr. Competitive), it also meant extra pressure to be the best

performer in the class. This was not

always achieved when the occasional nineteen-year-old-ex-gymnast yellow belt from Western Michigan University

would show up and whip off a double flying crescent kick without breaking a

sweat.

There

is a point, somewhere around green belt, where age and guile cannot keep

up with youth and flexibility. My prior

martial arts knowledge had held me in good stead up to now. However, I was beginning to learn new and

more difficult techniques that often required more than I could give.

One

day, we learned a new skill called a Tornado kick whereby one starts

with a roundhouse kick then spins quickly three hundred and sixty degrees into

another jumping roundhouse. Master Choi

demonstrated this with speed and grace and said it was now my turn. Right. Everybody backed away in anticipation of something big.

The

Olin locomotive started with a powerful, but totally uninspiring right leg

roundhouse (which never got more than belt high) followed by the famous

cockroach stamping footswitch from days of yore. Continuously moving, I spun around with the

speed of a revolving door and began to raise my right knee to complete the

maneuver. By now, however, I had lost

almost all of my turning momentum and was facing almost totally in the wrong

direction. I was in serious danger of

looking really bad or getting hurt – or both. Realizing this, and focused

primarily on not being embarrassed, I launched my kick as hard as I could,

hoping that it would help me finish the turn. Dumb move. My hip joint exploded

in pain. My kick shot out ninety degrees

from its intended target. And Master

Choi stood there – dumbfounded.

The

rest of the much-younger class went back to business, all performing Tornado

kicks with great balance and skill. At

times like these, one begins to satisfy oneself with the notion that he is in

this thing for “spiritual” reasons: to find greater wisdom and enlightenment or

some such other rationale.

In my position (age), I’m

not interested in teaching too much fighting

other than for self-discipline and

developing human character

through martial arts discipline.

That is the main purpose of my martial arts business today.

That is the main purpose of my martial arts business today.

Grandmaster Jhoon Rhee, age

68, March 2001

Once

one is a green belt, the number of classes needed for the next belt level

double from sixteen to thirty-two. I was

bound and determined that I would continue on my path as aggressively as

possible. I increased my classes from

three to five times per week.

At

this higher level of commitment, I was indeed learning skills much faster but

my body began breaking down. I was sore

all the time. My muscles ached. My flexibility actually became worse. I came down with frequent colds and my

concentration waned. I was at a

plateau. Many of my fellow students had

warned me that this would happen. I think

that perhaps, it was the realization of just how long and hard this road was

going to be.

I

tested for blue belt in December and passed, although I was not sharp and felt that I had

not completely learned my skills. The grading masters observed this and it was reflected in their critique of my performance. This was

hard to take because forms were my “specialty”. But I knew that Kwan Chang Nim’s (Grandmaster Chung's) criticism was right. I was tentative and

not on my game. I resolved to never test unless I was fully prepared, both physically and mentally.

Chapter

Six – Blue Belt

The wise

man, after learning something new,

is afraid to learn anything more

until he

has put his first lesson into practice.

Tzu Lu

Suddenly, I noted that my belts were getting shorter. The Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays had

taken a toll despite my training regimen. This really came to my attention when my January 2nd class

with Master Choi was the toughest ever. I was doing the same number of sit-ups but I couldn’t reach my toes like

I could a few weeks earlier. Ten pounds

makes a huge difference when it comes to Taekwondo training. I continued a five class-a-week schedule in

order to burn off some of that weight. By

the end of January, I was hammered by a major cold, which had become a serious

sinus infection and viral pneumonia. I

hated missing class but my body needed rest.

I took three days off.

There

were many times, while I was trying to fling my legs over my head doing

crescent kicks, that I asked myself if I had chosen the appropriate martial

art. There were many other combative

arts that required less agility and flexibility. Karate, for example, focuses more on hand

techniques and less demanding kicks. Tai

Chi is slower, more artful, and less rigorous for my joints and bones. There

were the grappling martial arts, such as Judo and the ultraviolent Brazilian

and African Jiu Jitsus, of course ... but I

never really liked putting my nose in someone else’s armpit or groin very much.

The

Korean martial art of Hapkido always interested me. I was getting a taste of it as part of my Taekwondo self defense training. I liked the higher level of sophistication of

technique and I appreciated the philosophy of redirecting the opponents’ energy. But Hapkido training involves a great deal of

throwing. The nights that we practiced Hapkido throws, I became extremely dizzy after being flipped about ten times or

so. I believe that years of scuba

diving, and the residual middle ear infections that I continually suffered as a

result, contributed to the vertigo I experienced from time to time in my

training.

I

think that I was very wise to have chosen the school that I did because I have

been privileged to learn from some of the best teachers in the area:

Grandmaster Chung, Master Choi, Master Chung (Mrs. Chung), Master Kim (from

Korea), Master Gonder, Master Siegel, Mr. Baas, Mr. Lipson, and Dr. Draznin.

A

very subtle, but not insignificant, thing happened while I was practicing my

blue belt forms. Master Choi, who normally

rode me pretty hard to execute kicking techniques correctly, was watching me

struggle with side-kicks in my Pyong-Ahn Sa Hyung form. I was having trouble maintaining balance and

kicking high enough. He gently stopped

me and showed me how to smooth-over my weaknesses when performing forms in

competition. In a way, I was relieved

that he seemed to understand my liabilities and accommodated me. On the other hand, I was angry with myself

that he needed to help me because I was not good enough to do it the right way.

When

the New Year arrived, we were told that testing procedures were going to be

much more rigorous than in the past. Now, in addition to the forms, self-defense, sparring, and memorization,

they added several physical performance tests.

If a student cannot keep up his physical conditioning between tests, he

will be punished with extra workouts. Although I appreciated the idea of raising the bar because it will

ultimately make Chung’s Black Belt Academy a better organization, from my perspective,

it felt like it was kicking a guy when he was down.

Indeed,

I had lost much of my enthusiasm in my quest for the black belt. I had worked so hard. I was tired, frustrated, and disappointed

with my slowing progress. Workouts were

getting harder, my body was giving out, and the goal seemed farther away than

ever. I was in a rut and was at risk of

burning out. And the number of classes required before testing had increased dramatically. I needed to make a major change in

strategy. From this point forward, it was

all about surviving. The sprint was over

- the marathon had begun.

One

day, it was announced by Master Joshu that the monk Kyogen

had reached an

enlightened state.

Much impressed by this news, several of his peers went to speak with him.

Much impressed by this news, several of his peers went to speak with him.

“We

have heard that you are enlightened. Is

this true?”

his fellow students inquired.

“It

is,” Kyogen answered.

“Tell

us,” said a friend, “how do you feel?”

“As

miserable as ever,” replied the enlightened Kyogen.

While

in Florida,

visiting my mother in Port Charlotte, I ducked

into several martial arts studios. One

of them, located in Punta Gorda, was a unique-looking Taekwondo do jang. Its

name was Florida United Tae Kwon Do School. When I walked inside the slightly run-down but

dignified cinder-block structure, I noticed several old pictures of the

school’s grandmaster – Sang Kyu Shim. Talking to the lady manager, I discovered that he had passed away

recently and that he taught in the Detroit

area for many years.

When

I returned to Michigan,

I asked Grandmaster Chung if he had known Mr. Shim. Indeed, Grandmaster Chung told me that Shim

was a fellow student when they trained together under Hwang Kee in Seoul. Shim was Chung’s senior by a few years and

was among the first handful of masters (including S. Henry Cho, Richard Chun,

Duk Sung Son, D.S. Kim, and J.K. Kim) sent by Hwang Kee and the other founders

in 1963 to open do jangs in the United

States. Mr. Shim, with help from his American sponsor Russell Hanke, opened his

first Tang Soo Do do jang on 8

Mile Road in Detroit.

Grandmaster

Chung told me that Hwang Kee respected Sang Kyu Shim very much because of

Shim’s high intelligence and personal discipline. While in Korea, Hwang sent Shim to teach the

U.S. Army because of Shim’s ability to speak fluent English. Once in the United States, however, Shim became

embittered toward Hwang, claiming that the founder was selfish with funds and

was not willing to promote Shim to higher status within the Moo Duk Kwan. Hwang asked Grandmaster Chung on many

occasions to speak with Mr. Shim in an effort to maintain Shim’s loyalty, but

they proved fruitless when Shim decided to change his alliance to join General

Choi’s International Taekwondo Federation (when Choi offered him a very high

position in the organization). A few

years later, when General Choi defected to North Korea, Shim returned to the

Moo Duk Kwan.

Sang

Kyu Shim attended college at Wayne

State University,

receiving a Masters degree in political science. He wrote several books on Taekwondo and was

Editor In Chief of Taekwondo Times magazine for ten years, until his

untimely death in a traffic accident. Grandmaster Chung attended Shim’s funeral and holds him in very high regard,

especially for the fact that Shim learned to speak fluent English in Korea, before

arriving in the United

States.

My work is a

reflection of myself.

My execution

of martial arts techniques

is also a

reflection of myself.

In whatever

productive work I do,

I will

create a masterpiece.

It will

reflect my genius and virtuosity.

In all

things I will work most seriously,

intelligently,

whole-heartedly

To it I

commit my soul, my body and spirit

and even my

whole life fortune.

I am a doer,

a venturer, a winner.

Grandmaster

Sang Kyu Shim

Personal

Creed

Chapter

Seven – Brown Belt

Grandmaster

Sun Hwan Chung – Moo Sool Do textbook

On

February 15th, I tested for 4th gup, brown belt, and

performed better than I expected - my forms were sharp, memorization was good,

and I knew my twenty-one basic motions.

Having

reached the 4th gup level, I was eligible to attend Instructor

Classes. The purpose of these

classes is to prepare the student to become an instructor. I had heard that these classes were extremely

rigorous, but they were mandatory to achieve a black belt. Warming

up before class was highly intimidating. Fifteen black belts spread around the room stretching, kicking the bags,

and doing advanced forms. I was a white

belt all over again.

As

it turns out, the class was a great learning experience. Kwan Chang Nim led the class personally. We worked on forms and self-defense,

stopping several times to discuss proper technique and teaching

methodology. It was enlightening to see

black belts as students.

When an

ordinary man attains knowledge, he is a sage;

when a sage attains

understanding, he is an ordinary man.

Zen proverb

Instructor

class also enabled me to learn more advanced skills in Hapkido. These methods involve more complex throwing,

joint locking, and breaking techniques. The term Hapkido translates to “way of

coordinating energy or power.” It

focuses on the development of internal energy, known as Ki, through

mental discipline, focus, and Tan Jon breathing. This controlled breathing helps to sharpen

the mind and channel energy though the body. Meditation is an important aspect

of harnessing Ki and promoting greater emotional stability and inner peace.

Continuing

my mental training, I bought the book, Living The Martial Way, by

Forrest Morgan. It intrigued me because

on the cover it said that it was a “manual for the way a modern warrior should

think." The author is a major in the U.S. Air Force. He cut right to the chase. He believes that the martial arts are not

arts, or religion, or philosophy. He

says that the martial arts are about war – about being a warrior. He makes the argument that practitioners

should train incredibly hard, be focused on annihilating ones enemy, and focus

on the more visceral and warrior-like aspects of the martial arts. He was highly critical of any martial artist

that was not focused on combat. He, of

course, was speaking about students like me that emphasized the

“intellectual” aspects of the discipline.

As

I read his book, I began to understand and appreciate his perspective. Perhaps, the martial arts were about

warrior-ship and I had not truly come to grips with that notion. Here I was, in a discipline entirely focused

on combat, aggression, and personal survival and yet I wanted no part of

that. I thought I was looking for mental

and physical discipline, deeper self-knowledge, and a sense of

accomplishment. There were many times, I

must admit, when I felt out of place in the do jang, in a room full of

warriors, all of whom relished and eagerly embraced the simulated battle of

sparring. I remembered when one of

Chung’s master instructors stood before a black belt class and arrogantly

expressed his opinion that if the student did not embrace and prioritize the

violence of the discipline, he was not a serious student of it. I found this disquieting to say the

least.

I

had thought of myself as a student, not a warrior. Maybe I made some sort of glaring

mistake. I tried to tell myself and

other students that I was in it for something “deeper” than the violence, but

that only seemed like paddling a canoe upstream. Was I the only one with this philosophy?

The fighter

is to be always single-minded with one object in view:

To fight,

looking neither backward or sidewise.

To go straight forward in order to crush the

enemy

is all that is necessary for him.

Daisetz

Suzuki

I

continued to plug along, attending four classes per week. I had settled into the longer periods between tests and it enabled me to focus on learning a multitude of new skills. These skills included multiple-spinning kick

combinations, speed drills, and higher-level terminology.

Slowly,

I began advancing out of my plateau. Master Choi told me that my technique with

my forms was excellent, better than most students at this level, and began

teaching me some of the finer points of the art. For example, we worked on hand

and foot timing so that each motion would finish crisply and with more power.

He also noticed that sometimes, I held my breath during forms, often finishing

tired and winded. I knew that this was bad technique but I was focusing on the

forms themselves that I was not remembering to exhale at each impact point. I

did my forms a hundred times more using correct breath control until it became

second nature. It actually helped to improve my focus and timing.

On

several occasions I was helping more advanced belts to relearn forms and

terminology that they had forgotten. I felt encouraged when my instructors had

the confidence in me to demonstrate the skills for the class. I must admit that

I had a moment where I watched myself perform the twenty-one basic motions in

front of a mirror and was impressed with the power and confidence that I

projected. I was making progress again, that is until the week of May 7, 2001.

I

had been doing five classes a week and was getting less winded during

workouts. My excess winter weight was

coming off as well. At the same time,

however, I was experiencing chronic soreness in my ankles and feet. My neck was always stiff. My hamstrings were constantly tight and

required long periods of stretching. On

the first Monday in May, I was practicing jumping roundhouse kicks when I

landed wrong on my right leg, hyper-extending my knee. This was not good because I had been favoring

my left knee, which had filled up with fluid in the past few weeks. Surprisingly, I was able to continue with

classes and stay on track.

…On

track until the next Thursday, when while sparring against a yellow belt, I

launched a left-footed front kick toward his midsection. He lifted his right leg in defense and I

jammed the ball of my foot into his kneecap. Pow! He fell to the floor grabbing

his knee. I limped in circles. We

continued with the match and ended class. It was not until after I had showered

and walked out to the car that I realized the extent of the injury. By the time I had arrived home, a mass of

swelling was erupting from the bottom through the top of my foot. The foot was turning purple. I could feel intense pain in the center of my

foot. I had fractured bones in the ball of my foot behind my toes.

In

two days I was scheduled to compete in Chung’s Annual Forms Competition.

I really

enjoy sparring, but I realize that your body doesn’t heal

the same way after

you reach a certain age.

I like to spar with the students at the seminars

I like to spar with the students at the seminars

but the problem is that they like to go heavy

and then I have to go heavy.

I don’t feel like taking chances anymore.

I don’t feel like taking chances anymore.

Bill

“Superfoot” Wallace

Professional

Karate Association World Champion

On aging and

sparring

Saturday

morning and my foot was one third larger than normal. My toes were swollen together. It was discolored purple and black across my

entire instep and around the side toward my heel. It was too sore to wear a Tae Kwon Do

shoe. Warming

up, I found that it hurt mostly in the jumping portions of my poomse. With some extra focus, I could get through

it.

I was competing in the final group, against a twelve-year-old green belt and a

twenty something purple belt. Getting up

after sitting cross-legged on the floor for nearly two hours, my foot had no

feeling in it. I limped up in front of

the judges and pounded my way through Pyong Ahn Oh Hyung without a glitch. It wasn’t my best effort, but it wasn’t a

disaster either.

I must be

worthy of the great DiMaggio who does things perfectly

even with the pain of

the bone spur in his heel.

Ernest Hemingway - The Old Man and the Sea

In

the end, I finished second behind the twelve year old. Of the five judges, I scored first or tied

for first with three of them. One judge

killed me, and that was all it took. I

asked my daughter, Michelle, if she noticed a problem with my form. She said, “No, it was good, except that when

you punched, your belly-fat jiggled a little, maybe that was it.” Yes, it was direct … but honest. The truth hurts.

Chapter

Eight – Brown and White Belt

Three

days after the forms competition, I tested for 3rd Gup. The swelling was going down on my foot and

the purple color was changing to a sick-looking yellow. I was well prepared for the test and gimped

through my forms, basic motions, and sparring without incident. I impressed the kids with a powerful speed

break on a one-inch thick board. A few days later, I was presented with a brown

and white striped belt.

At

this level, I learned a new and difficult poomse form called Bassai,

which has fifty moves. This Tang Soo Do

form was created more than 450 years ago by the monks of the So Lim Sa temple

and is signified by the cobra. It begins with a unique Joon Be stance, hands

clasped together and motioned in a semicircle. I learned this new technique in the three weeks after my belt test. Several steps were made more difficult by my

still-injured left foot, which burned with pain whenever I landed on it. I couldn’t think about that now, I was to

compete in the Great Lakes Cup on June 22nd – less than two weeks

away.

As

I signed up for the tournament, I noticed that sparring competition was divided

into age groups. My group went from 33

years old to 43 years old. Furthermore,

at my gup level, I qualify as an “advanced” student. Just my luck. Forty one years old and I get to play with the youngsters! My stomach started to turn inside out.

To conquer

fear is the beginning of wisdom.

Bertrand

Russell

I

was getting good sparring experience in the Instructor Classes that I attended

every Wednesday night. Although these

classes are for students 4th gup and higher, I was often the only

gup rank in the room, the others all being black belts. What I learned mostly, however, is how much

more I needed to learn! My flexibility

and sparring speed were pitiful and I looked ridiculous attempting double and

triple flying spinning back kicks. But

if commitment were measured by sweat, I was tops in my class. It shouldn’t have mattered, but I wondered

many times what those black belts thought of me grinding away in the back of

the room.

The

2001 Great Lakes Cup took place at Lansing Community College, the same location

where I competed the year before. More

than three hundred martial artists from all over the Midwest

were there to test their mettle. Our

“seniors” flight was to compete in ring number five but there were so many

competitors that half of us were sent to a makeshift ring in the far corner of

the gymnasium. Three “volunteers” were

hurriedly selected to judge our forms. One judge was no older than maybe sixteen years old. He was from an Illinois Taekwondo

organization. The other two judges were

extra scorekeepers from other tables and were given this duty at the last

minute.

I

was in a group of six advanced gup students.

Every competitor did the same form, except me. I think they were performing the ITF* Palgye

form for that belt designation. I

performed the Tang Soo Do Bassai form. I thought that I had done it flawlessly:

crisp, strong, no hitches or problems.

* International Tae Kwon Do Federation. Our students belong to the World Tae Kwon Do

Federation. There was one Taekwondo

organization until 1974 when the ITF and WTF split. ITF headquarters moved to

Montreal, Canada. WTF headquarters

(Kukkiwon) remained in Seoul, Korea and is the recognized Taekwondo sanctioning

body for the International Olympic Committee.

As

I snapped into my joon be position, I knew that I was certain to win the gold

medal. Then I overheard one judge ask

the other what my form was. Then I heard

the other say “I dunno." Then the first

one asked, “Well, which one was harder?” and the other pointed at the

competitor next to me. That was all she

wrote. I did not win the gold. I did not

win the silver. I did not win the bronze. I

was stunned. I felt gypped and wondered